[The AMAIC considers this article as interesting, though not necessarily true,

and would certainly not date Amenhotep son of Hapu anywhere near as early as c. 1350 BC]

Posted by: Editor on Sep 18, 2009 |

In Egypt, the return of agglomerated (geopolymer) stone1300 years after the Great Pyramids,

under Amenhotep III and Akhenaton (18th Dynasty).

Divine incarnation in carved stone became the rule under the New Kingdom around 1400-1200 B.C. and the hegemony of the god Amun. The soft sandstone from the Silsilis quarries, used for in the great temples at Karnak and Luxor, is so easy to carve that everything appears simple. So why should there be any controversy about the monuments and objects dating from this period? Because some are made out of an extreme hard material: quartzite!

It is true that 1300 years after the great pyramids, agglomerated stone, geopolymer stone was again being used, albeit sporadically, under the domination of Amun. After all these years, the worship of the god Khnum and initiation into his mysterious technology had not been forgotten. The greatest Egyptian scientist-architect-scribe, Amenophis Son of Hapu (1437-1356 B.C.), eminence grise of the pharaoh Amenhotep III, XVIIIth Dynasty, re-introduced it and used his alchemical (geopolymer) knowledge to build amazing statues made out of quartzite with geosynthesis and geopolymerisation. And the heretical king Akhenaton, son of Amenhotep III, did the same in order to rival the supremacy of Amun by forbidding carved granite stone.

....

The clues for geosynthesis (geopolymerization), artificial quartzite stone

Geologists fail to agree between themselves in determining the origin of the quartzite stone used to the famous colosses. To summarise, French and German archaeologists/geologists claim that the Colosses of Memnon were sculpted in a quarry 70 km further south down the Nile and that they were brought up by boat. Other British and American researchers propose an even more extraordinary exploit. According to them, the statues were carved, then transported upstream on the Nile from a place 700 km downstream near to Cairo. Each team of scientists uses more and more sophisticated methods in pursuing their research, including atomic absorption, x-ray fluorescence and neutron activation. When applied to the most enigmatic of Egyptian monuments, these new techniques shed more confusion than light.

In Antiquity, the statues commanded respect; the colosses of Memnon are monoliths: they are made from a single block of stone weighing nearly 1000 tonnes and standing on a pedestal of 550 tonnes. They are 20 metres high, equal to a seven storey building. The stone from which they are made is quartzite, which is practically impossible to carve. The members of the Egyptian expedition organised by Bonaparte at the beginning of the nineteenth century recorded several notes on the stages and on the Egyptian quartzite quarries. Thus we can read in La Description de l’Égypte :

“None of the great quartzite blocks bear any trace of tools that is so common in the sandstone and granite quarries: a material that is so hard, so refractory in the face of sharp tools cannot, it is true, be worked by the same methods as ordinary sandstone nor even of granite. We know nothing of how the blocks of such a rock were squared, how their surfaces were dressed or how they were given the beautiful polish that can still be seen in some places; but though we cannot guess the means, we are no less obliged to admire the results. There is nothing that can give a better idea of the highest state of advancement of the mechanical arts in antiquity as the beautiful execution of these figures and the pure lines of the hieroglyphs engraved in this material, harder and more difficult to work than granite. The Egyptians recoiled in front of none of these difficulties; nothing seemed to hinder them; the working is free throughout. Did the sculptor, in the middle of engraving a hieroglyphic character, strike one of the flints or pieces of agate that are encrusted in the material, the line of the character continued in all its purity, and neither the agate nor its enveloping stone bear the slightest crack.”The consequences of this last observation are very important. What is the technology that could enable hieroglyphs to be engraved in this way? The Pharaoh Amenhotep III puts these statues down to a “miracle”. Later on, in hieroglyphic documents, the stone is designated as “biat inr”, which means “stone obtained after a miracle”. To what miraculous technology is Amenhotep alluding?

Once we accept the geopolymerization technique we can understand how Amenophis Son of Hapu, was able to make this quartzite rock and cast to the colosses of Memnon, these enormous statues more than seven storeys high. With the technique of geopolymer stone, we can also explain the controversy surrounding the different interpretations of the analysis results obtained by various scientific teams.

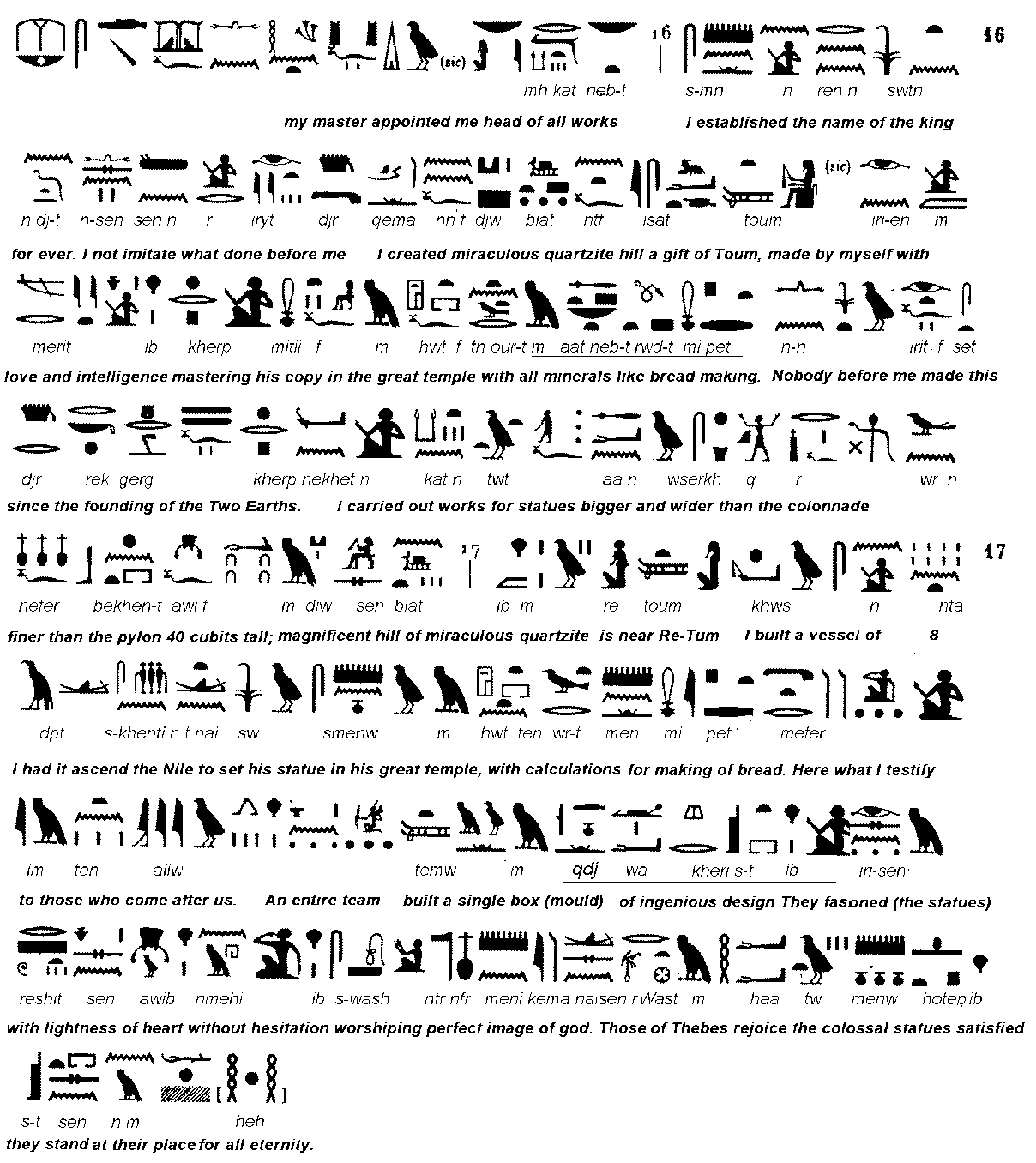

On his biographical statue at Karnak, Royal scribe Amenophis (1350 BC) describes the building of these colossal statues by the technique of agglomeration (geopolymer stone) “as bread is made” using a box (a mould) specially made by his workers. Here are lines 16 and 17 of his biographical inscription, in a translation by Joseph Davidovits, which differs from that of egyptologists (see Inscriptions), because they were unable to interpret the technical key-words:

“My master (the Pharaoh Amenhotep III) appointed me head of all works. I have not imitated what was done before me. I created a miraculous quartzite hill a gift of Tum, made by myself with love and intelligence, mastering his copy in the great temple with all minerals like the making of bread. Nobody before me has done such a thing, since the founding of the Two Earths. I have carried out work to make statues of great girth and taller than the colonnade, finer than the pylon 40 cubits tall; this magnificent mountain of miraculous quartzite is near Re-Tum. I had a vessel of 8 built and I had it ascend the Nile to set its image (its statue) in its great temple, according to our calculations (with the technology), as for the making of bread. Here is what I testify to those who come after us. An entire team built a single box (mould) of ingenious design. They fashioned (the statues) with the lightness of their heart, without hesitation, then worshipped the perfect image of the god (pharaoh) thus created. Then came those of Thebes, rejoicing in the colossal statues and satisfied that they would stand for all eternity.”

New translation by Joseph Davidovits (technical keywords are underlined). Egyptologists translate the technical key-words “making of bread” involving the word “pet” into “enduring like the heavens”, which means nothing (see the traditional translation by egyptologists in Inscriptions). The bread making technology refers to the use of a pasty material that would be worked out like dough to produce geopolymer stone ....

....

Taken from: http://www.geopolymer.org/archaeology/civilization/colosses-of-memnon-masterpiece-by-amenophis-son-of-hapu